06 Mar 2015

These classes, according to the degree of enlightenment at which they have arrived, may propose to themselves two very different ends, when they thus attempt the attainment of their political rights; either they may wish to put an end to lawful plunder, or they may desire to take part in it.

In 1850, Frédéric Bastiat wrote his famous work, The Law. This book centered on his observation that legal frameworks, and the violence used to give them weight, were being used to pursue not simply the application of justice, but increasingly the pursuit of what he called “legal plunder” – the act of using coercion to redistribute property. This distinction is emblematic of a great divide between how people remedy our various societal ills, and the above quote succinctly summarizes this divide. There are those who see legal plunder as a problem in and of itself, and there are those who, for better or worse (and with a hefty dose of egomania), don’t like where society’s boat is going, and are simply hoping to get their hand on the tiller. It goes without saying that I fall in the former camp, and I’m writing this to explain my critical take on the discussion around gentrification in my city to date.

I have a friend who lives in San Francisco, who I occasionally keep abreast of the goings-on in Nashville, and she often casts an amused eye on our growing pains. For someone who lives in SF, our housing crisis seems downright quaint, by comparison. Larger cities have been undergoing this process for generations – San Francisco itself is undergoing another in a seemingly endless series of transformations. For a peek into the sort of future that awaits us (if we continue on our current path), please read this article. Read all of it. Understand how they got there – how each iteration of policymaking was another layer on the ball of wax. This phenomenon is not new, and I have yet to see a proposal for our city that hasn’t been tried a dozen times over in cities like SF, with dreadful results. (Seriously, ask anyone from San Francisco about Prop 13 sometime - there are plenty of people there with dumb opinions on it all too)

But before we get into the proposed solutions, what is the actual problem? What is gentrification?

Amidst all the debate in Nashville, I haven’t seen an article that defines it particularly clearly (at least, not on purpose). Because I couldn’t really even find a coherent summary of the actual problem, I asked, on twitter, a while back (with a clear agenda of some subsequent socratic questioning in mind). Among the myriad responses, you can see a lot of common ideas: “rich people kicking out poor people”, “white people kicking out black people”, “it’s simple progress”, “developers are evil”, and so on. These are glib answers from people with tongues half planted in cheek, but they do pretty accurately represent the depth to which we probe the issue (i.e. not very). Personally my favorite glib definition is “change I don’t approve of”. But I digress. For the purposes of this conversation let’s broadly identify two (of many) camps of people who can be affected by the various forces that coagulate under the term “gentrification”: there are lower/middle-class (often minority) people who are literally forced financially to relocate their home, and there are people who dislike changes to the “character” of their neighborhood. It’s the former that I am primarily interested in – often this category overlaps with the latter, but just as often, the latter are indirect beneficiaries of the gentrification they so revile.

Nashville’s media is, naturally, shining a light on the issue, albeit obliquely. A brief tour of some of the more recent pieces on the problem, focusing specifically on how they frame/define the problem and what they propose as a solution:

- Steve Haruch, “High Rises vs. Honky Tonks”

- The Problem: a heightened focus on growth has raised property values, which developers are capitalizing on, and Nashville is losing its soul

The Solution: ?? (I think Steve’s article was more just a sad lament than a prescription)

- JR Lind, “Priced Out of Nashville”

- The Problem: Nashville is desirable (“It City”) – people that came to Nashville for low cost of living can no longer afford to live here.

The Solution: Not rent control, possibly more affordable housing, mostly Nashville will become so expensive that it will lose its allure and the problem will solve itself. (I think JR had a swiftian proposal for a wall at one point, but I can’t find it.)

- Abby White, “Everybody knows Nashville is hurting for affordable housing. What are we gonna do about it?”

- The Problem: “rising property values also mean rising property taxes — and higher costs all around” (direct quote)

The Solution: Abby here covers a variety of recent suggestions: NOAH’s three-point plan: “preserve and produce affordable housing through recurring funding for the city’s Barnes Housing Trust Fund, inclusionary housing policies and creative uses of federal, state and local funds. Second, offer means such as home repair assistance, property tax relief for longtime residents and homeowner education to prevent people from losing their homes. Finally, create a structure of accountability for affordable housing needs.”

- Bobby Allyn, “As high-dollar houses crowd onto tiny lots, teardown fever is sickening neighborhoods across Nashville”

- The Problem: Old houses are getting torn down and replaced by newer, more expensive ones (roughly)

The Solution: affordable housing requirements for developers (via interviews with residents)

- James Fraser and Amie Thurber, “Nashvillians should have the right to stay put”

- The Problem: One third of households in Nashville do not earn enough to afford the market rate housing available in our city.

The Solution: Mostly the same as NOAH’s stated ideas above.

Lots of words, but very few new ideas. In general, the proposed solutions generally tend to revolve around a few core policy ideas: means-tested inclusionary zoning requirements that mandate lower rent for certain income brackets, and property tax “relief” for certain categories of residents (a brief moment of lucidity here). They are essentially legislative band-aids that ignore the root of the problem, and simply hope to carve out exceptions to remedy a short laundry-list of perceived ills. They’re laudable attempts, or at least they would be, were there not so little evidence that any other city has had any measure of significant success with them.

And yet, despite the aura of bewilderment pervading the discussion of the roots of gentrification, the actual, literal problem is right before us, and it’s tremendously simple and terribly direct: property taxes are forcing people out of homes they own, or rent. Property taxes raise the barrier to ownership, and disincentivize (or essentially prohibit) continued ownership. That’s it. But actually talking about this is oddly verboten – even discussion of property taxes as a problem at all are in the context of temporary, limited and selective “relief” for the taxation. It’s taken as a given that property taxes exist and must exist – a sacred thing; a veritable force of nature. But, they’re not, and they aren’t a fact of life – not any more than gentrification is, and they are two sides of the same coin. They are the cause of this phenomenon: the literal plunder of one party by another, acting collectively. There is no magic in this world, only the actions of human beings and their consequences. You cannot turn a blind eye to the source of the problem while simultaneously condemning it. If you believe that property taxes are as much a certainty as death, you are supporting the process of gentrification. If you believe that the moral way to administer human activity is by the action of elected representatives who direct this coercive plunder, you are the gentrifier.

So what to do? This is where you expect, I assume, that I will deliver my Grand Solution. I don’t have one. How could I? It’s quite a mess we’ve all made of things, really. The morally correct course of action is, of course, to do nothing (Literally, I mean: dismantle and/or ignore the system of coercive regulation). Barring that seeming impossibility, the opponent of gentrification should consider the next best thing: reducing the imposition of property taxes on the owners of valuable property. I realize the phrase “owners of valuable property” in your mind will conjure the developer fatcats in their infinite expanses of high-rises, but in this context I literally mean the people we are (supposedly) concerned about protecting: the lower-middle class, often minority, property owners and renters who are literally forced out of their homes.

Will there be negative externalities? Yes. Will there be unintended consequences? Yes. Will we have to figure out a better way to fund our daycares-slash-prison-camps schools? You bet. Will upper class accumulated capital find loopholes and exceptions to maximize their acquisition of land and squash any hope of easing the little guy’s tax burdens? Probably, yes. This is a horrible house of cards we’ve built and dismantling it without hurting people is difficult, if not impossible. It may be an awful and impossible problem to detangle, but you cannot blunder around pretending, wide-eyed, that no one knows what the source of the problem is. You know what the problem is. Fix it, or get out of the way. If we believe, as James Fraser and Amie Thurber claim to in their Tennessean op-ed, that people “should have the right to stay put”, then by all means give them the right: the right to own and retain property.

12 Dec 2014

Humans are really bad at appreciating scale. Let’s take a look at human evolution and population growth.

Homo sapiens sapiens emerged as a distinct species, say, sometime around 200,000 years ago. Let’s call it the year -197986.00 BCE. We’ll ignore the millions of years of evolution of our predecessors and competitors that preceded our step into the spotlight for now.

For reference, all of “recorded history” (written) has happened since roughly 4,000 BCE. That means that humans have existed for a timespan roughly 50X that of all recorded history.

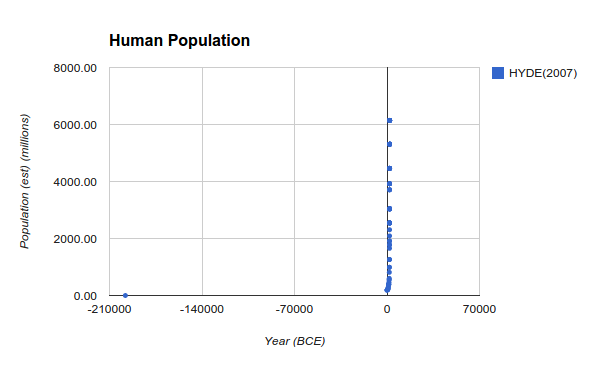

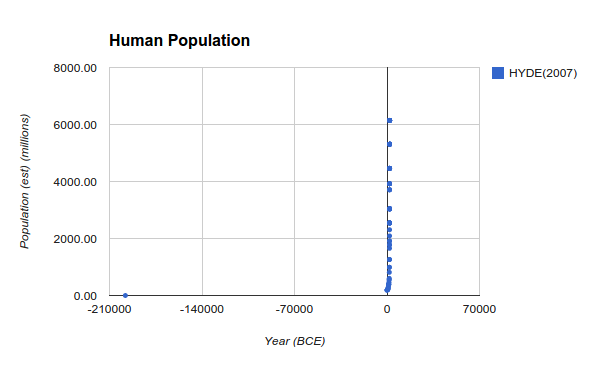

Here’s a scatterplot of human population since -197986.00 BCE:

So uh, yeah, not very useful, is it? That’s because all of modern history happened entirely in that remarkable upshoot at the right of the graph. During the 196,000 years prior, we were all still noodling around on the plains of Africa in relatively small numbers. The explosive growth of human technology, the correspondingly exponential growth in population, and everything we know or theorize about “human civilization” has occurred in that tiny fraction of the time our species itself has existed on this planet. On an evolutionary timescale, it’s a very small chunk of time, with a near seismic level of change and upheaval, which requires logarithmic scale to even start to visually appreciate. What can we take away from this?

- “Human nature”, such as it exists, represents the culmination of millions of years of evolution, culminating in humans that are, like their predecessors, social animals, optimized to organize in small bands of a few dozen to a few hundred individuals. This is not a prescription for social policy or a prediction of the future in a world in which we have billions of individuals, but it may very well be a limiting factor for how we organize.

- Any proposed system of ideal human social arrangement based on anything that occurred since, say, 4,000 BCE, is based on a view that is cripplingly myopic. It’s making a predictive assumption based on recent, unprecedented growth and dynamic emergent patterns.

- In short, if you’re assuming stasis or ideal arrangement based on any point on the above logarithmic-scale growth, uh .. you’re probably wrong.

16 Nov 2014

Intro

Years ago, during the beginnings of Nashville’s hot chicken renaissance, Jim Ridley posted a simple recipe for a basic portion of nashville-style hot chicken. Not much to quibble with, on the whole, except possibly the choice of chicken breast as the medium (people eat chicken breasts?). I was intrigued, and thus my quest to replicate my favorite hot chicken was launched. I wrote this a few years ago, documenting my first large-scale attempt to make it. It didn’t go badly, but it wasn’t quite right, either. Specifically, in thinking of hot chicken as a uniquely southern dish (which it is), I looked up a recipe for traditional southern fried chicken as the base. This was a mistake. The result was a buttermilk-brined, very thick double-dredged method resulting in a very thick, bready crust. The combination made for a bready sweetness that competed with the heat and made a chore out of peeling away/eating the breading before you could even get to the meat.

So what, then is the goal? Opinions vary, but in my mind, the archetypical Nashville-style Hot Chicken requires a thin, flaky breaded crust, and my preferences reflect this. Prince’s and Hattie B’s more or less represent the gold standard in this regard. This is a photo of a “Shut the Cluck Up” leg quarter from Hattie B’s:

You can see in that photo the flaky ridges of crust providing a home for the tasty cayenne goodness, without presenting an overwhelming barrier to the chicken itself. It’s a beautiful thing – basically, they do it right. Turning fried chicken into hot chicken is quite easy, but it’s the replication of this particular style of fried chicken that has proven most challenging to me.

So, rather than post a traditional recipe, I’m going to break this post out into various parts of the recipe, including areas that are more/less contentious, posting my experience with them.

To Brine or Not to Brine?

- Wet brine: It’s hard to go wrong with a good ol’ fashioned brine of water + salt + herb/spices. One complicating factor with chicken is the crispiness of the skin, and I have found that a wet brine can result in soggy skin.

- WINNER SO FAR: Dry brine: A different approach is to simply mix up your herbs/spices with salt and sugar in a large ziplock bag or container, shake vigorously and let it sit overnight. This yields somewhat the same effect of infusing with flavor, but has the added benefit that the salt draws some of the moisture out of the skin. The downside, in my experience, is that if you let it sit too long (even overnight), the chicken meat itself can get too dried out, resulting in a rubbery texture after cooking. Note: rinse the salt/spices off of the chicken and pat it dry before breading + frying.

- Combination? I’ve contemplated doing some sort of overnight wet brine + a briefer dry brine w/ salt to let the skin “air out”, but at that point it really sounds like more work than it’s worth.

- No brine: This is always an option. Does brining really make that much of a difference? Hard to say. Don’t feel guilty if you don’t bother at all – chicken is pretty tasty and moist as it is.

The Breading

- Simple flour dredging: Pretty much what it sounds like, this simply involves dredging the chicken in all-purpose flour. You have to be careful to let the chicken sit for a spell (>30 minutes at least) to let the flour start to bind to the skin, otherwise it will all fall off while frying. I’ve not had a lot of success with this method – flour still tended to fall off, what crust did form was a spottily-covered flat/homogenous crust.

- Flour dredging + egg wash: my next experiment was to take the aforementioned flour dredged chicken and apply an egg wash + another dredging in flour. This yielded a more substantial crust and a fairly nice-looking final product as seen here. Aesthetically, this is as close as I’ve come to breading that resembles the chicken I’m after. The failing of this attempt was that the crust that formed was not very porous and had a brittle, hard texture that didn’t soak up the sauce and wasn’t super pleasant to bite into.

- Southern-style buttermilk dredging: As mentioned above, just .. don’t do this. Not for this kind of chicken.

- WINNER SO FAR: Cleverer Sciencey flour dredging (i.e. korean-style fried chicken): This was my most recent experiment, and I think it holds the key for a future final product. This attempt was loosely based on the instructions here for making a korean-style fried chicken wing. The goal is to use a careful combination of baking powder, salt and corn starch, letting it rest and then coating with a thin vodka/water-based batter. Read the linked article for more than you probably want to know about the science behind all this, if you like. The result was a nice, porous crust, though still a bit thicker than I intended (I think my batter was low on water). It was also rather homogenous and lacked the “flakes” so visible in my ideal fried chicken. I suspect that a combination of this method with an egg wash might be the final answer.

Frying

- There isn’t a lot of contention (that I know of) when it comes to frying the chicken. Use an oil with a high smoke point. I use peanut oil that I save in my fridge after filtering for repeated use. I’ve heard that some people use chicken fat, though I would wonder about the smoke point of that?

- I fry in my cast iron skillet. I want to upgrade to a dutch oven at some point both to avoid burns from the bottom of the currently shallow pan, and also to reduce the risk of grease fire spillage.

- Try to peg the temperature of the oil at around 350F. It will drop when you add the chicken.

- Don’t overcrowd the pan. This was almost pushing it for me, especially since I am using a shallower skillet and not a dutch oven, so my oil doesn’t have a lot of thermal capacity. If you add too much at once, the temperature will drop, and you will get nasty chicken.

- Can you bake the chicken if you want a healthier alternative? No.

The Sauce

Ah, the sauce. This is what turns regular fried chicken into Nashville hot chicken. As I’ve said in the past, there’s nothing particularly magical about it – the dish mostly leans heavily on seemingly obscene quantities of powdered cayenne pepper. The basic recipe, as also detailed in the recipe linked above:

- A few tablespoons of lard, microwaved to soften

- Powdered cayenne pepper – exact quantities are hard to give, here, but you want enough powder that the pepper itself with the lard starts to form a thick paste. Don’t be shy here. If you’re not scared of it, it’s not Nashville-style hot chicken.

As with everything, though, connoisseurship abounds, and there are some decisions to make.

- Cayenne or other peppers? Despite its household status, you really can derive a truly staggering level of heat from cayenne via quantity alone. But there is an upper limit, and clearly the hot chicken establishments in Nashville add Something Else for their upper echelon heat levels. Naturally, I have no idea what they add (I’ve heard it rumored that Hattie B’s shut-the-cluck-up involves ghost peppers). I’m a traditionalist, so I think most of the flavor should come from cayenne, but if you want to kick up the heat, you’ll need something else. I’d avoid any peppers that are smoked (I made this mistake with ghost pepper flakes once), since it turns the flavor into something else.

- Oil or lard? I didn’t really know this was a thing, but more and more recipes I see are starting to call for a sauce made with oil instead of lard. I’ve even gone to a few newer hot chicken places that are clearly using oil. I am deeply opposed to this. It was obvious that the chicken I had was made with oil, because the sauce tasted more like peanut oil than cayenne. Nope nope nope. I’m not opposed to some judicious supplementation of oil to make the paste a little runnier (some people use frying oil), but the base should be lard, in my opinion. The point is to have something to saturate with cayenne, so your chicken is thus saturated with cayenne, not to saturate your chicken with oil. That’s just gross.

- Sweet? I’m torn on this, partially because adding too much sugar was a huge fail the first time I made hot chicken, and the trauma runs deep. I think a little bit of sweet in the sauce is fine, but a little goes a looooooong way. I sometimes just put a few teaspoons of honey in mine. Don’t overdo it.

- Other Spices? Similarly, the first time I made hot chicken, I mixed in all sorts of go-to spices, in line with my usual “the more the merrier” madcap approach to cooking. It wasn’t bad, but certain spices go a long way towards changing the flavor profile, and you can’t be reckless here. Garlic powder can quickly overwhelm everything. These days I don’t add anything, except for ground mustard powder, which was an excellent tip from hot chicken judge and affluent west nashvillian of note jrlind. As he said, mustard helps make the heat a more nasal experience, rounding out the masochism of it all. Every place and person probably has their own mix of spices they do add, but I’d be judicious and sparing – nashville hot chicken flavor is largely about the cayenne.

Serving

Serve on a slice or two of white bread, with pickles. Pickles not shown. But don’t forget the bread. It soaks up the sauce and is arguably the best part!

That’s it! Happy eating!

09 Nov 2014

I am reluctant to dip my toe into this – with all the gamergate nonsense going on, rational, level-headed discussion about gender issues and violence seems hard to find (for my part, I’ve managed to maintain a stubborn ignorance of gamergate, as it seems like a colossal waste of time).

You may have heard recently that a man murdered a woman recently, and uploaded the photos to 4chan. Megan Seling wrote about it here. As with most articles on PITW these days, it quickly turned into a shitshow of trolling and insults. I just have a few things to say here, then, rather than wading into the quagmire there:

The point/crux of the article as far as I can tell is an attempted segue from the news story (“man murders woman, uploads photos to internet”) to the conclusion.

First, this segue, as far as I can tell, is a nonsequitur, starting roughly here:

The reason Kalac’s actions feel so much more shocking than other recent tragedies is because they manage to bring together a number of women’s rights issues – the devaluation of women, domestic violence, and a woman’s right to privacy – into one stomach-churning trifecta.

It doesn’t bring those things together, though – or at least that connection is not demonstrated. If you say that A “brings together” B, you have to explain how – saying something doesn’t make it so, as I have mentioned on twitter as well. What follows is a collection of other unrelated instances of man-on-woman/women violence presented with no connection other than “a man murdered a woman”.

He clearly didn’t see much value in his own life, but what is so much sadder is that he saw even less value in Coplin’s life. A man’s right to have a woman, and not be betrayed by that woman, is outweighing a woman’s right to life at all at an alarming rate, and that is fucking terrifying.”

and further from the comments:

In both cases, the woman is not being seen as human, but rather a lesser being for the man to treat however he wants. That’s what makes it a woman’s issue over a basic human one.

It’s absolutely true that he devalued her life – that’s what murder is. Murder is the ultimate culmination of the devaluing of life. It’s necessary but not sufficient to make this a “woman’s issue over a basic human one”. It’s not entirely clear to me what Seling’s conclusion is saying with respect to ownership and “outweighing”, but my best guess would be a contention that Kalac’s crime and other crimes reflect a rising rate of domestic violence/murder. This, however, is demonstrably not the case – women killed by intimates has been decreasing since 1993. To be sure, there are still real issues of gender inequality and violence, but weak or flawed causal inferences like these do a disservice to genuine awareness campaigns. If that’s not what she is actually saying, I’d love some clarification..

As the world comes online, we will have more and more windows into things – both horrible and wonderful – that were already happening all over the world. It’s easy to mistake our increased visibility into incidents with a rising trend. It’s horrifying to see domestic violence, and we should continue to try to eliminate domestic violence, but it would be a mistake to think that increased awareness/visibility means a rising trend.

27 Oct 2014

Sony NEX-5N w/ Voigtlander 50/1.1.

Is this a professional camera?

Hi there! So, you want to have a photography policy. You’re holding an event or you manage a venue and you want to protect or restrict what sort of photography can be done and what can be done with the photographs. Excellent! There are a lot of reasons for this – some better than others:

- Safety – too many photographers in general or photographers in the wrong place can be dangerous, or at least annoying.

- Flash photography – can be very irritating.

- Intellectual Property – you want to protect your brand and are afraid that people taking photos will diminish it, or you’re afraid someone will see a photo of whatever your venue is hosting and not go to it instead. This is stupid, but ok! I respect your dumb concern.

As an amateur/hobbyist photographer and frequent event attendee, I can give a few pointers what not to do in order to annoy people attending your thing:

“No professional cameras”

This makes no sense – people are professionals (sometimes), not cameras.

“No cameras with detachable lenses”, “No big cameras/SLRs”, etc.

This is a relic of a bygone era – a weird and nonsensical attempt to discriminate professionals from amateurs based on their camera. Even many consumer-grade cameras have removable lenses, and many professionals use cameras with fixed lenses. If I glue the lens onto my camera is it suddenly ok? High-quality cameras are ubiquitous these days – trying to prohibit them entirely is a losing battle.

What your actual policy looks like of course will depend on your concerns (see above), but please stop using gear as an arbitrary substitute for prohibiting what you actually want to prohibit. If you don’t want flash photography, prohibit flash photography. If you want to own all the photos taken, make everyone sign (or post?) a waiver of rights to any photos taken. If you don’t want photography, ban cameras (good luck with that). Thanks in advance!