consumption

17 Mar 2004Over at [HobbsOnline][1], in a [post about the presidential candidates and tax policy][2], I made a somewhat offhand comment, not knowing what I was getting myself into:

All Bush gets blame for is selling a tax cut as a recession-fighting measure when it in fact was not a recession-fighting measure, but was instead a massive tax-cut to the rich with a bone thrown to the middle class.

Read the whole thing for the entirity of the context, but in short, a discussion ensued, some of which was civil and some of which was not, wherein I laid my case that although Bush sold his tax cut as a recession-fighting demand-boosting economic measure, it was anything but.

[slartibartfast][3], representing the more civil half of the discourse, was adamant in getting me to elaborate both on what I thought was wrong with Bush’s tax policy as well as what I would do differently. Inevitably, the discussion meandered towards the largest criticism of the Bush tax cuts: that they are heavily tilted to the rich. While some even try to debate this (which is quite silly), the more reasonable debate is whether or not giving money to the rich is an effective way to boost aggregate demand in the economy. I claimed that it was not, laying out an off-the-cuff layman’s view of my opinion of reaganomics’ (lack of) success as well as some common-sense as for why I believe that:

Here’s what I mean. Say that you have $1000 in tax cuts to distribute. Let’s assume the cost of living per some arbitrary unit of time is $100.

You could give $1000 to one person that is wealthy. Assuming, for the moment, that the wealthy person spends $100 of it like anyone else on necessities, but the other $900 is superfluous. So, you can be confident that the $100 will be spent, but you have to hope they feel like buying $900 worth of luxury goods to make up the difference.

Now take that same $1000 and give $100 to 10 lower/middle class people that are currently $100 short of the cost of living per this unit of time. These 10 people will each spend the $100 on the cost of living alone, and you have no superfluous money left.

Your confidence level in how much demand you generate is much higher. You quite literally get more bang for your buck.

Make sense?

I was then asked if I had any hard data to back this up. While I felt like he was trying to paint me into a corner, it’s clear now he wasn’t, and was just looking for some hard data. I certainly can’t fault him for what. Critical thinking – you gotta love it. It forced me to do some research about the assumptions I was operating under, and what empirical data exists to support them.

So, while I posit that it “makes sense” that you would get more aggregate-demand bang for your tax cut buck in the lower/middle class, is there any empirical data to back that up?

The short answer: yes. But first, let me make a clear distinction about what we’re talking about. There’s a term in economics called “average propensity to consume” (APC) that is simply a percentage of consumption / income. What I am focusing on is the difference in APC by income class. i.e., which income class has a propensity to spend the largest percentage of its income, all other things being equal. What I am not focusing on is changes to these incomes in either the short-run or the long-run. Indeed, the latter is actually a giant source of contention – with a perfect “consumption function” being the holy grail of many an economic crusade. Friedman’s “permanent income theory” in this case also stands as a giant red flag for the viability of a tax cut as a short-term demand-boost, but that’s a debate for another day. (Hint: he theorized that people tend to save, not spend, windfalls until they are confident their income is “permanently” increased – which is why Bush wisely makes a big deal about making the tax cuts permanent.)

Now, I knew in the back of my head that it was a fundamental given in any consumption function that as income bracket increases, APC decreases. This is pretty easy to find mention of in just about any intro macro-econ course, for example from [this one][4]:

AVERAGE PROPENSITY TO CONSUME

The willingness to use a proportion of income (Y) for

consumption (C) is known as average propensity to consume (APC):

APC=C/Y

As income increases, the average propensity to consume

decreases. This is indeed observable in the fact that wealthy

individuals consume a smaller proportion of their income than to

poorer people who may in fact be force to receive money from

others.

What I had a much harder time finding was the actual data. It’s very difficult, as it turns out, because most data is focusing on the margin – the effect of relative changes in the income of consumer units themselves on aggregate demand.

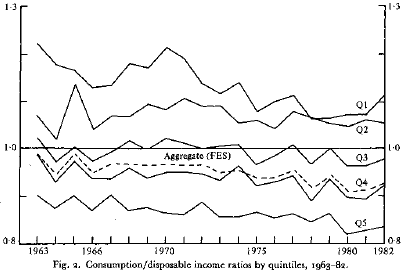

But, it’s out there. Using data from the Family Expenditure Survey (FES) in the UK, an analysis of expenditures as a percentage of disposable income by income quintiles (Q1 - lowest; Q5 - highest) was performed [1][5]. The results are pretty conclusive:

Here we see a definite pattern: the highest income brackets spending the least percentage of their income, and the middle quintile breaking even. Interestingly, the lowest quintiles spend more than they receive in income. The paper explains this odd phenomenon:

It is impossible for a fixed group of households to continually spend more than it currently receives. The above-unity consumption/income ratios for the lower income quintiles are only sustainable, as shown, because the household groups defined in this way, as quintiles of the current income distribution, are not fixed. Three different types of household might be found in the lowest quintile. One type consists of the ‘permanently’ poor households – households who start life with few or lowly rewarded natural endowments and who never receive, throughout their lifetime, transfer payments sufficient to lift them above the bottom of the distribution. It is unlikely that the consumption/income ratio for ‘permanently’ poor households is much different from unity.

The other two main types of household in the lowest quintile are the ‘contigently’ poor – they are there for a part of their lifetime, but not for the whole of it. There are two such types corresponding to the two ends of the life-cycle. At the ‘young’ end there are households able to spend more than their current receipts because they can borrow against future earnings. Relatively, however, it is households at the ‘old’ end of the cycle who dominate the lowest quintile. These are retired households able to spend more than current receipts by dissavings from wealth accumulated during their active earning lifetimes.

So, that explains the lowest quintiles above the break-even point – retirees and borrowers.

So, it seems to me that this data provides pretty solid empirical support for my opinion. I would find it difficult to make a case for the demand-boosting effects of a tax cut mainly for the rich, given this skew, because rich people spend less (and save more) of their money, pure and simple.

Now, I did find a paper which attempted to empirically verify the effects of active income redistribution on aggregate demand, where the data available is even murkier and more difficult to isolate from other factors. (Which seems to consistently be the problem with developing a consumption function for marginal changes in income or wealth.) The results, therefore, are less conclusive [2][6]:

Let me begin with a confession. At the outset of this research I hoped to establish:

PROPOSITION A: The marginal propensity to consume of an individual falls as his disposable income rises.

And therefore:

PROPOSITION B: Out of any given total disposable income, a larger share is spend on consumption when income is more equally distributed.

As it turns out, while both theory and empirical evidence lend at least some support to A, they do not support B. In fact, as I explain shortly, Proposition B does not follow from Proposition A. What does follow is a similar-sounding proposition:

PROPOSITION C: If income is taken from one individual and given to another individual who is identical in all relevant respects save that his income is higher, then total consumption will decline.

So, more evidence, albeit less conclusive. Bear in mind, I am no economist, but I find this all terribly interesting. I also think it’s terribly important: the idea that wealth redistribution and a healthy economy go hand in hand is important. A tax cut largely for the rich is disturbing to begin with, even if it does help the economy. If it doesn’t, it’s inexcusable.

Thanks! Your comment has been submitted and will appear shortly.